Ismatu Gwendolyn: Class Traitor

Show Notes:

Twenty Enemies by James Forman

the role of the artist is to load the gun

you've been traumatized into hating reading (and it's making you easier to oppress):

Information Anarchy: The Case Against Sponsorships

hello and welcome to Threadings!

…the newsletter-podcast where I explore the seams on this world, and where I fit into these systems. This is the first iteration of Threadings that is a video essay and I think that that’s fitting; do let the record show I never, ever re ally wanted to become a video essayist. But you all, witnessing me, change me all the time, whether I am ready to change or not.

Do grab your tea; I have here a rooibos loaded with dried fruit and florals. I’m here to answer a question from a member of my constituency.

Short answer: of course they don’t lose the ability to be radical . Every artist has the ability to be radical at any point in time. It’s never really a question of whether people are able, it’s a question of whether people are willing.

a brief introduction

My name is ismatu; I am a very specific person in a very specific circumstance. Two things I am not: (A) cultural critic (B) stand-in for the general public. I am not performing a persuasive piece. I am here because I am a young revolutionary, and I am an artist. You and I are in a particular rhythm here, where you trust me with your mind for a small and invaluable loop of time and I do my best to be useful to you within that trust. With this time, I am here to talk to you about the contradictions of liberalism within contemporary art-making, and over the course of this essay, I will explain to you how I have made myself into a class traitor. And then, we will renegotiate our social contract.

We’re gonna talk about: (1) the context of this video, (2) the BUY MUFFINS phenomenon, (3) the necessity of precarity.

…after we define some terms.

One of the guiding resources I used to construct these arguments is Twenty Enemies by James Forman. Forman’s revolutionary CV is longer than my forearm, quite frankly: Executive Secretary of SNCC, Minister of Foreign Affairs in the BPP, and position holder within Black Economic Development Conference, League of Revolutionary Black Workers, and Black Workers Congress. I find this pamphlet to be immensely valuable as a young person with revolutionary goals, particularly in how helpful it is in defining what revolution is. There are a few terms I’m going to use throughout this essay which have wishy-washy colloquial meanings because of how widely they are used. Those specific political terms are: revolutionary and liberal. The term radical is not explicitly defined in the text, so I pulled together definitions from outside sources.

Radical in political use means to depart significantly from the systems we have in place. It means you have the intent to transform or replace fundamental elements in society and position yourself to do so— much like a radical electron, in science, can change the basic composition of an atom by adhering to a different system. You can tell pretty easily if something is radical because it will meet significant institutional pushback. The systems we have in place are engrained because everyone participates; someone refusing to participate and actively creating a new thing also creates an open threat to the system we have in place. Radicalism that’s detected by our overarching system is met with pushback.

Then, as defined by the text, you have revolutionary and liberalism. Revolutionary action seeks and works towards seizing the power of the state. That’s on page one, sentence one.

This is also, actually, a good statement of purpose: whenever I say something that makes people uncomfortable, or irritated, or whatever within video format, viewers who are otherwise unfamiliar with me and my work ask me why I made the video. This, the keeping of my modes of logic and opening them for meaningful critique, this is why. I do not monetize my videos and I don’t spend time on social media for fun. I am here for the work of the masses. If we are talking about a people’s revolution, a popular uprising, then are talking about seizure of state power for the good of the collective mass. And those discussions mean we need to teach each other how to do so, in real time, which means I must study the revolutionary experiences of others and make available my own revolutionary experiences.

Liberalism is defined by Forman as “the refusal to engage in principled ideological struggle inside and outside of a revolutionary organization.” (pamphlet page 13).

Forman argues that liberalism must be eradicated if we are to create a successful revolutionary organization and greater revolutionary society. Liberalism is inherently destructive because it may posture, it may give lip service or aesthetic credence to radical, revolutionary ideals, but there is no spine. There is no follow through to seize state power. Often, the desire to overturn that power and redistribute it completely is not present at all; liberals benefit materially from the systems that racial, gendered capitalism has in place. They don’t have a desire to deviate from them, even if they benefit from pretending like they could.

Remember the specific definition of these words as we move through these thoughts.

Some scene setting:

The stage is set for war on United States soil; war-making happens in policy long before there is ever any live ammunition. I’m witnessing an open coup from one of my homes while I gaze from across the Atlantic Ocean, safe in another. It feels eerily reminiscent of watching the world talk about Sierra Leone’s civil war— or better said, the war of attrition that was waged on recently independent Sierra Leone to take control of its diamonds. The political circumstance is not copy paste, but I…once you begin to see the parallels within interally-hostile governance, it’s hard to unsee.

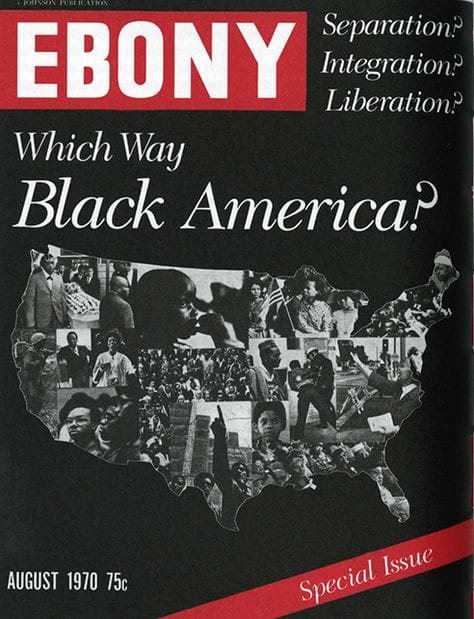

Anyways, war-making never begins with guns. It begins with policy and it begins with culture. Four central elements to the struggle to build a society (as emphasized by James Forman): politics, culture, economics, and militia (pamphlet page 13). We have a coup taking place from a foreign billionaire, a United States government that has many tentacles across the world growing a bit weary, and the soft power of the US still quite strong— especially within their use of the Black Music MegaStar.

That last bit— the Black Music MegaStar— that’s the cultural context in which I write to you from. It’s February of 2025. The militarist powers of the United States are looking rough: we’re supporting the war in Ukraine (for the purposes of controlling their resources), the apartheid regime in Israel, and getting embarrassed by the Houthis in the Red Sea, as well as a good, old-fashioned cold war with China.

I actually began this essay in the summer of 2023, when I was watching campaigning for the Harris administration, backed by the Black MegaStars, feeling bile grow in the back of my throat. The conversations that we have online remain cyclical because we have no political teeth with which to chew and swallow our food. We move like cattle chompin' cud. “Are these people making propaganda? Are our Black MegaStars championing the US empire?”

…Yes. Of course they are. Their excellence within their craft, nor their very authentic Blackness, does not erase their liberalism. In fact, it makes their liberalism even more insidious.

BUY MUFFINS

I explained this in the short-form, but I’m not certain I was clear about where I was making the comparison, and it’s been a while since I first introduced the concept. So: in high school, my speech and debate team utilized this fundraiser on our scrolling school announcements to sell muffins for our tournament fees. I was a first year and found the advertisement confusing— it didn’t say where or when to buy the muffins, or how much they cost, or who was selling them. I wasn’t sure it was effective. I learned a very valuable understanding of marketing from being dead wrong; the advertisement was so effective we raised way more than the amount we needed initially.

None of those pesky purchasing details ended up mattering. What sold the muffins was the amount of conversation dedicated to the advertisement as a whole. The upperclassmen thought it was hilarious watching the younger grades squint at the screen, trying to make sense of the swirling gif. Many of them were reading George Orwell’s 1984 in class. Everyone thought it was so funny, how “tongue in cheek” it was because the advertisement is openly trying to hypnotize you. And, because the upperclassmen especially could not stop talking about it, do you know what they did?

They bought a fuck ton of muffins.

In stating that I don’t engage with the art of millionaire-billionaire artists, I compared their art to this buy muffin advertisement. Political in nature, right? Designed to spark conversation. By choosing to watch it, repeatedly, choosing to talk about it, choosing to invest emotionally in the successes of Black MegaStars, we consider their flourishing under capitalism good for our collective good, despite the fact that many of us can no longer deny the exploitation capitalists must employ by the design of the economic system. When we engage, repeatedly, we are training our brains to think these people are very, very important and necessary and good. And thus, they become powerful.

Black capitalists benefit from Black revolutionaries; Black revolutionaries never benefit from Black capitalists.

There is no part of my life that benefits from letting liberal capitalist art-makers inject their worldviews into mine. Liberalism is a mold, a fungus upon revolutionary desires and operations. Once again: I, ismatu, am not a disembodied voice and pen. I am speaking to other people who are deviating from the systems that we have in place. I am speaking to people who wish to learn more about revolutionary action as it’s previously manifested and how we might apply that to our current circumstances. This pamphlet was published in 1970 and every word is still relevant today.

There is a reason I have not named a particular artist, or put their pictures up or what have you. It’s because this essay is not about those artists; I am to write about you and me, to consider who I become as I come into increasing positions of power and what I owe to you, to us, we the masses whom I love so much.

When you see something repeatedly, and you hear conversation about it everywhere, and you yourself talk about it, you are telling your brain that this hyper-visible thing is, in fact, really important. Remember that I am a particular person in a particular circumstance: I am a mental health provider trained clinically in a traditional master’s of social work program and, through continuing education, now trained in hypnotherapy and neurolinguisitc programming. It does not matter how tongue in cheek your critiques are, or how impermeable you believe yourself to be. What you see, especially what you see repeatedly, shapes your brain. It shapes aspirations. It shapes what you believe is good or possible. It influences our decisions far more than we would ever feel comfortable admitting. Art is everywhere! Under capitalism, we just call it “advertising."

I don’t listen to millionaire-billionaire art. I don’t watch their media. I don’t engage; I do not need to and I see no desire to. And I used to! Of course I have relished in my fair share of popular culture. I didn’t stop paying attention out of principle, or because I wanted to make a statement, or because I felt like I “should." I stopped engaging because I was radicalizing, truly, permanently, in my precious mental space. And engaging with millionaire-billionaire Black Megastars, who continually put on radical aesthetics as a literal costume yet move economically and politically as liberals, as people whose only desired change within the system is to see a few more Black billionaires created, leads to too much cognitive dissonance for me to be able to enjoy the art.

The original question is: where is the line for you? What happens if you follow an artist and they make it big— can they still be radical? Can they still be a revolutionary?

Of course they can. They possess the ability to and they definitely know what they cannot say without risk censorship, de-platforming, or demonetization from institutional bodies. One thing that ultrarich Black artists are? Investors. They participate heavily in the stock market to be able to grow their capital such that their spending can never outrun their fiscal growth. In order to meaningfully engage in the stock market, you must have two things: (1) an understanding of geopolitics, because the stock market is about predicting trends, which means you must understand what is happening in the world or you must have a team that does, and (2) skin in the game. Reward requires precarity. Significant reward requires significant precarity, always.

Creation of a new society is also something you invest in; you stake your power, your various capital, and your time in the construction of new things. Meaningful radical action also requires understanding of geopolitics and willingness to accept risk. We know they understand geopolitics (and I refer to these artists in the plural because each artist is actually a multi-national company of people producing their performance). Particularly for our seasoned Black MegaStars, we know their teams study Black traditions and history such that they produce deep, decadent art. You don’t have access to this much knowledge and capital and remain politically illiterate. They do not practice liberalism because they don’t know any better. They practice liberalism because what member of the US-born and made ultra-rich class member do you know that actively seeks the fall of the US empire? What?

Girl yes they are making propaganda!! Why do we continue to discuss this!!

They could be radical; they have no desire to assume that risk, the guaranteed blowback. Whatever personal desire they may or may not have to invest in a revolutionary future become overshadowed by the interests of their multi-national businesses. So they are liberal and yet they dress like radicals, they compare themselves to radicals, they even perform little moments of self-awareness, stating they they know they are not the powerful revolutionaries the public seeks out so much, and still seek to posit themselves next to the aesthetic, because they know that their visibility alone will convince the many who watch that they are what they appear to be. And they benefit from that association. All that garners them the social capital necessary to continue to move as Black capitalists.

If this essay is not about these artists, why are you discussing them?

Because in discussing them, I discuss us. I can take a pulse on our greater culture by understanding how much liberalism we celebrate, and if not celebrate, tolerate. How many of us still leap to defend the class that oppresses us actively today because we still wish, one day, to become them. How even if we don’t want to defend them, many of us still associate freedom and peace with US dollar bills instead of associating freedom and peace with a day where US dollar bills don’t exist at all. That’s why I care! I’m talking about us. I want us to stop settling for the cosplay of revolution, but I know we only do so because we find comfort in that excellent, excellent escapism. So I have two tasks:

(1) As a revolutionary, my job is to make sure that we are well equipped to believe that revolution is not just possible, but probable. That we have systems that will support you through the backlash should you choose or need to deviate. That we, in February of 2025, are living through another wave of worldwide uprisings. Don’t we remember the largest organized strike in history, the farmers in India that brought their country to a halt? That was just four years ago. They’re protesting again. Did you know?

Didn’t you see the popular uprising that took place in Bangladesh? Led by the students and the people? That was July! Just eight months ago! Did you know their interim government was installed? That they continue to move forward?

Did you see that Khartoum was seized back from the RSF in Sudan? The Sudanese popular uprising was only in 2019. God will see them through to the next people’s government, inshAllah.

These are the events that soak me in hope. These are the events that turn me towards the music of Rhita Nattah, of Dead Prez, of Le Grand Kallé and Miriam Makeba and Sun Ra. I have gone from finding comfort in escapism to finding comfort in knowing what is fully, fundamentally achievable within my lifetime. As a revolutionary, my job is to teach us how to want to seek comfort in a world that we make rather than this world that we see.

(2) As an artist, it is my job to tell us useful truths. Everyone always misquotes Toni Cade Bambara; what she said was, “As a culture worker who belongs to an oppressed people, my job is to make revolution irresistible.” As an artist, my job is to make art so excellent and expansive and truly loving— art as a love song to the way I feel about us, we, the masses— that you want to begin looking for and making with your hands that which you cannot see.

I start with the recognition that we are at war and that war is not simply a hot debate between the capitalist camp and the socialist camp on which economic, political, social arrangement will have hegemony in the world. It's not just the battle over turf and who has the right to utilize resources for whomever's benefit. The war is also being fought over the truth. What is the truth about human nature, about the human potential? My responsibility to myself, my neighbors, my family, and the human family is to try to tell the truth. And that ain't easy.

There are so few truth speaking traditions in this society in which the myth of Western civilization has claimed the allegiance of so many. We have rarely been encouraged and equipped to appreciate the fact that the truth works, that the truth works, that it releases the spirit and that it is a joyous thing. —Toni Cade Bambara, 1983

As an artist, my job is to make art so excellent and expansive and truly loving— art as a love song to the way I feel about us, we, the masses— that you want to begin looking for and making with your hands that which you cannot see.

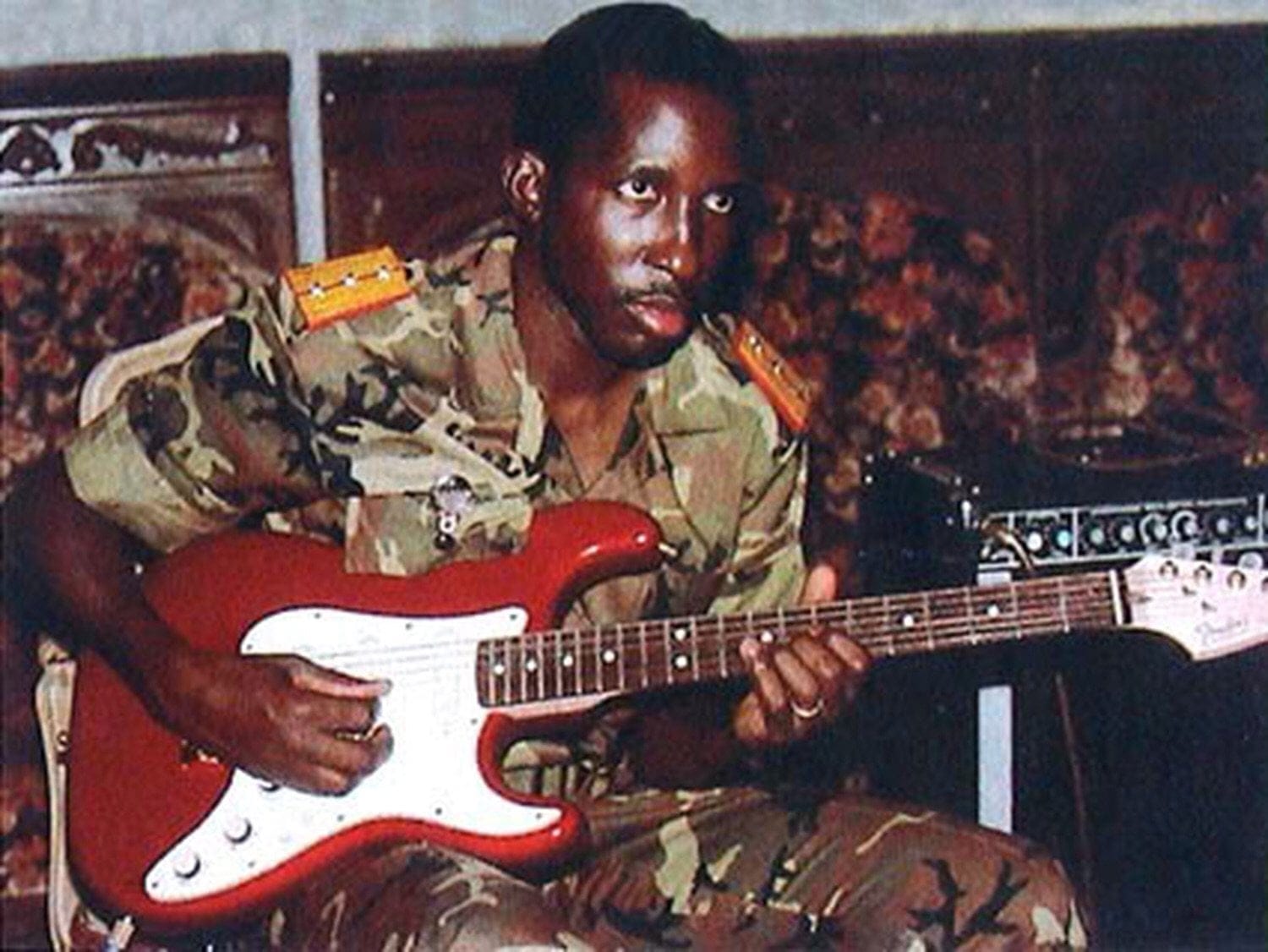

Thomas Sankara, Amílcar Cabral, Rashid Mahdi and Nina Simone all walk into a bar.

I believe revolutionaries get a dive bar in their shared heaven. I believe they have the wars on like sports game, cheering and sighing and groaning at the pulls and pushes of liberatory armed struggle, death having now become a peaceful, laughing thing. I imagine their combination would be a chance encounter— Sankara and Cabral sitting at a booth, enjoying a stout, discussing their pick up football matches and Nina walks in with Lorraine and Billie and they haven’t seen each other in a long time! And they’re all giggling over a long cigarette (you’re allowed cigarettes in heaven, but only once per week), and Rashid is somewhere in the corner, thinking himself inconspicuous, snapping film through the twilight haze. In heaven, the sun is always just setting at this bar and death isn’t so bad now such that everyone laughs and drinks and smokes some. These are the people that teach me that art is a necessary weapon, that I must betray the ideals of the petit bourgeoisie and join them in the sharpening spear. I want to laugh at death like that. I want to believe they read the essays I write two years from today and go, this! This is something worth discussing over a beer at the bar.

Class Traitor: an individual who betrays the ideals of the socioeconomic class they belong to

Thomas Sankara talks about class traitors in his political orientation speech of 1983, when the August Revolution was a success, when he addressed his newly liberated people over the radio.

When he broke down the aspects of the Voltaic society, who their people, their masses were vs. who were enemies of revolution, members of petit bourgeoise sat on the fence. He argued that some of these trained members of society could be convinced to come over to the side of liberation; they fear the empire’s hand as much as it feeds them. Sankara argues not that the revolution will be won by class traitors by any means, but that class traitors (those in the trained professional class who might use their training for the people) are a necessary part of any revolution. He himself was a military school graduate turned general, and general to prime minister. He betrayed his class to become to first president of Burkina-Faso.

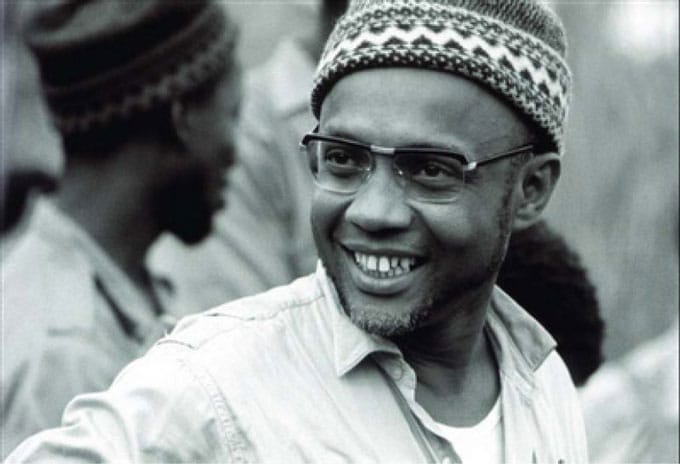

Amílcar Cabral does the same thing twenty years before.

He, from Portuguese Guinea, goes to college in Lisbon and becomes one of few in his starting class to graduate with the concentrated study of agronomy– then spent years spent covertly building a political base, covertly using the skills he learned as a pencil-pusher to build out systems where his peoples could not just own their means of production, but the process of ideation behind the production. He argues that if you own not just the means of production, but the means to ideate what that production should be in the first place– and until you are able to do that, someone else is writing the history of your country for you. I hope he cheered on his country’s victory over a beer on the other side.

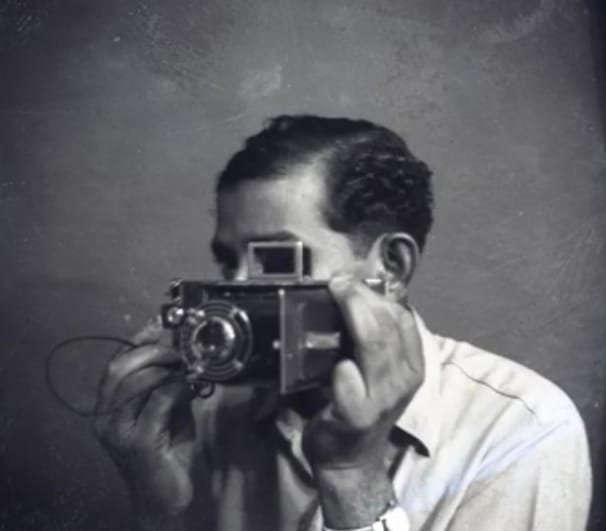

Rashid Mahdi’s photography helped to usher in the Sudanese uprisings in the 1960s,

—simply by capturing what was relevant to Sudanese people. His lens is often referred to as the golden age of Sudanese photography, where he captured at his studio everything from family portraits and birthday celebrations to demonstrations in the street. As I argue in the role of the artist is to load the gun, Dr. Bedour Algaraa lays out plainly the way that revolutionary art made available to the masses precedes revolutionary uprising by the masses. Art teaches us what is possible, conceivable, achievable. Worth paying attention to.

And Nina…

I have such love for such a complex character. I already wrote an essay on her, who traded her good and proper stardom to sing protest song after protest song. Exclusively. Mississippi Goddam was just the start.

This essay is about us, about me. What is the line and the threshold for me personally? As I continue to experience an expansion in my stage, a rise to acclaim?

Renegotiating the Ismatu Gwendolyn Contract

I think that radicalization is the point in time, not in which you begin to think different things, but the point in time in which you are willing to do different things.

So where's the line? Now that you know that your masses can see you, and they love you enough to invest their time and attention and their ideas and dollars and conversation and their trust in you. What do you do with that love? What do you do with that trust? Where do you stake and invest that trust? Is it through the building of personal systems that you can create comfort for yourself individually? Or do you find a way to subvert those systems?

Remember, revolutionary act is one that seizes power from the state. Radical acts are one that deviate from the systems that we currently have in place. So I need to renegotiate the Ismatu Gwendolyn social contract. You all have given me a stage and that has provided me with capital. You all give me your very precious resources, right? Your time, your attention, your engagement, and for some of you, your dollars– and it has set me on what could be the route of a very traditional celebrity. The route of the traditional celebrity is to press on every bit of monetization that is available to me. I'm supposed to sell you things. I'm supposed to walk in advertisements. I'm supposed to ensure that you buy my art, to make sure that it is all behind a paywall so that you buy it for money. I'm supposed to garner as many streams of income as I conceivably can to offset the precariousness that comes with being hyper visible or highly visible because it's not safe. It's straight up not safe. So I'm supposed to use you all as a site of endless extraction to be able to create for myself private systems and private comfort. Okay. That's the route of a traditional celebrity: to press every button of monetization as I possibly can.

And the route that I have chosen creates precarity for me as I resist the illusion of safety that comes with privatization. But also the route that I'm taking creates farms in Sierra Leone. And that is so dope. It creates a new mode of being in public or revitalize at least expectations in our public figures because it should be okay to expect things of our public figures. This is something that I see all the time. Well, why do you need our public figures to be revolutionary? Why should we expect anything from our artists? ...Because they expect things from us. They expect us to uphold them and to applaud them and to give them our very, very, very precious time. So why don't we get anything on our end of the contract? Why is it foolish or idealistic to be able to expect things from the people that are representing us on the world stage?

Do I not owe it to everybody involved in the Ismatu Gwendolyn Experiment to push the envelope, to try out a new form– or rather actually to return to an older form of public existence?

So I'm doing something odd. I've written a book. You all have really wanted me to write a book and to publish it as a means of supporting me. And that is very sweet. That means a lot. I… instead of doing that, I'm going to take all the money that this book provides and literally give it all away. Lol!

This book that I've written, it's very good. And I was, approached by agents and traditional publishers to be able to do it in the normal way. But the problem with the normal way, two things: (1) it required me to sell my intellectual property, which means that I don't really get to control what happens to most of the money that the book makes. And it also (2) means that I am relegated to the celebrity activists, right? Where I say radical things, but I'm kind of pigeon-held in this circumstance where I don't get to do radical things because I don't own the work. And furthermore, I don't really believe that information can be owned. I know that I talk about Information Anarchy: The Case Against Sponsorships a lot, but it's really one of the best essays that I've ever written. The process of writing it radicalized me and the process of returning to it radicalized me. I kid you not.

I'm choosing to self-publish small prophecies because I want to make sure that I retain as much money as conceivably possible over the art. And all of that money is going to building out that universal basic income project in Sierra Leone that I've been talking about. I want to make sure that the subjects of the book benefit from the book itself, which should set that I think that that should be the standard in the industry. In undergrad, when I originally did this research, I didn't publish it under my undergraduate (or my graduate institution!) because that would mean that the Institution itself gets money and I get praise and the people that the research is about get nothing. And that is not satisfying to me. Support is not just intellectual and it's not just about visibility even though those things are important. Support is material; meaningful material support creates systems. So a universal basic income program that is crowdfunded can create a system for three years, but a universal basic income program that is funded by royalties can create a system for a really long time.

Releasing in audio format first– if I've learned anything from writing on the internet, it's that people have an automatic stress response to being invited to read something. And that's okay, I don't fault you for that. Whether I think that that is right or wrong or productive or not productive that we don't know how to read, we don't know how to read. So I'll read it to you.

This is kind of…wild? I certainly have never seen anyone do this before, at least not in my lifetime. Usually by the time an artist donates the entire proceeds of a particular work to a particular cause, it's (A) on the charity model, and (B) when they're already like multi-millionaires. And I am not that. I am not that. However, I think that I have the opportunity to create some new blueprints for us here to raise our collective standards for what we can expect from our artists and from the people that claim to be revolutionary. You got to act like it, right?

See the contract terms below:

- instead of a traditional print run with a traditional book publisher (which I was offered at multiple points), Ismatu Gwendolyn retains the full rights to the artistic work(s) they have stewarded and breathed life into. Small Prophecies will be known to the public in the following ways:

- as an audio project in four separate steaming albums, made free everywhere you are able to stream audio projects (including but not limited to: Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube, Soundcloud, etc.). The debut in audio format helps to invite the layperson to engage with artforms that come with structural barriers to access or comprehension (engaging with long-form text, reading poetry, or navigating learning/reading disabilities).

- the E-Book and PDF versions, which requires no overhead costs for distribution, will be made available for free. This ensures that the book is accessible worldwide, including in places where any amount of United States dollars for a book is an untenable expense. This also includes those of us in the imperial cores who would love to partake, but cannot spare the money to buy a copy.

- Ismatu Gwendolyn, the transcriber of the work Small Prophecies, does not consider themselves to have sole proprietary ownership over the work. This is because the work was built collaboratively, through many years of life experiences with many different teachers. As a result, the print copies (which do require overhead) will garner a profit (typically known as royalties). Ismatu Gwendolyn will keep 0% of royalties for personal use. 100% of royalties will go towards building out the Universal Basic Income program in Sierra Leone for Ebola Survivors, the central population within the book’s narratives. This allows for a stream of income for people otherwise too disabled to work. Then, should funds raised from book sales exceed $400,000, 50% of the royalties thereafter shall provide continued support to agriculture efforts in Sierra Leone, helping to alleviate the chronic food insecurity that Ebola survivors (and many others) face every day. Ismatu Gwendolyn has been working on a rice harvest since December 2022. In 2025, that first harvest will come; there are talks to expand to corn and other kinds of produce.

- I dream of fruit trees!! Thinking of little ismatu, who assumed that by 26 I would be dreaming of impending nuptials and children. LMAO no baby child!! You are dreaming of giving your grandmother her first bowl of raspberries! look alive!!

Conclusions

We, the masses, lack radical imagination.

Liberation is still something that we conceive of in US dollar bills, in American styles of comfort. We imagine freedom and what we see is comfort, which is how you know that these world-makers are absolutely winning their never-ending war. They manufacture what we think is possible, such that it never occurs to us to want something more than or beyond what we see.

And so, both culturally and economically, I am tasked with living out an answer to the question of the revolutionary artist. The question is never really about ability, is it? The question is always: what are you willing to do?

I hope the work of your day allows you to take comfort in the work of your hands tomorrow.

Or, better said,

peace.

ig

a moment I cut out of the essay:

We, the masses that keep me up at night. That is how I love you all. You know I lose sleep thinking about learning plans for you? It’s the same loving rage that a teacher I adore once described to me, years ago, in my first year of high school. She told me she was up staring at the ceiling fuming, keeping her husband up, raging well into that deep night with how angry, how heartbroken she was that she had a class that never wanted to think farther than what was in front of us, when we could. That’s how I love you. I lose sleep at night thinking about what I must write next, how I must read and re-read that revolutionary or those accounts, my parents are sick of death of me on whatsapp, going on and on about what I think we’ve almost grasped, where I have to challenge myself, where I failed to make my point clear. If I could open my skull and show you how much I think of you– all the time. All the time.

Works Cited (unlinked):

Jensen, E. (2005). Teaching with the brain in mind. ASCD. Chapter Three.

Pugh, Jonathan, ed. (2009). What is Radical Politics Today?. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 9780230236257.

Grill-Spector, K., Henson, R., & Martin, A. (2006). Repetition and the brain: neural models of stimulus-specific effects. Trends in cognitive sciences, 10(1), 14-23.

Member discussion