The Mythical Black Artist™

Otherwise entitled, “Everyone inspired by Nina Simone; Nobody singin’ Mississippi Goddam.”

Welcome to Threadings., the newsletter and podcast in which I explore the seams that keep my world from fraying apart. Recently, I poked my head out of my chronically-offline hermit shell existence at the same time that Beyoncé did… something? A Netflix show? Football… something? I’ve divested from art that makes me itch to see money as the way to liberation and I’m not regressing on that, so forgive my ignorance. I do, however, see a familiar cycle of conversation reinvigorate itself, and I want to throw some ink in the ring.

What I am here to write about today is the recurring discourse we have about the Black artist, and the devices they use to make themselves marketable across audiences, and ways we allow ourselves to be taken for a fool lapping that shit up. Because everyone wants to be Nina Simone; nobody wants to sing Mississippi Goddam.

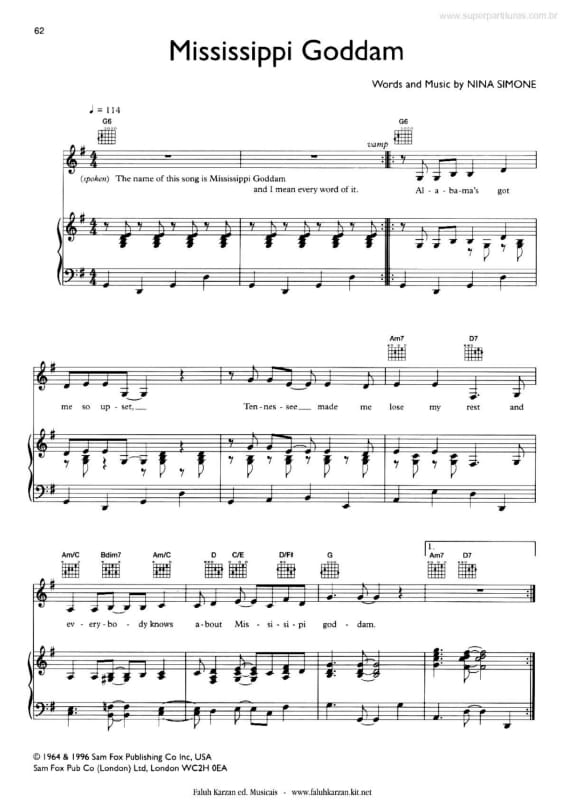

Let’s roll back time. It’s 1964 in the United States of America (the existence of the country looking dicey as it is). March, specifically. This month, Cassius Clay has rejected his slave name and donned Muhammed Ali, given to him by Elijah Muhammed of the Nation of Islam. It’s the same month that Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life in prison, that Malcolm X resigned from the Nation of Islam, and the very same month that Lyndon B. Johnson (having taking the presidency after Kennedy’s assassination just months before) signed the Civili Rights Act of 1964. Nina Simone, a breakout star at the top of the decade, has been captivating audiences in live shows, on television, has organically grown to the top of the charts. Her voice is distinctive, blooming, grating. It sticks with you. You hear it on the radio as news from the Viet Nam war rolls in between songs to cheer you up, reminding you of love, lust, the blues. There is a new Nina Simone song that she sang for the first time in February of 1964. In March, just one month later, she performed it to a mostly white crowd at the Carnegie Hall, a venue she had always dreamt of occupying.

Though, as a girl, she wanted to be the first Black female classical pianist to play Carnegie. And she was there, however there was nothing classical about it.

Nina Simone, known as the High Priestess of Soul, decided to do something prolific Black music artists had not. Which there were plenty of at the time. Motown was a worldwide phenomena. Soul music, Negro music, was topping charts everywhere. The only thing more widely sung and loved was The Beatles, those sweet buffoons. You had Aretha Franklin, Gladys Knight, Diana Ross and the Supremes, you had Etta James and Otis Redding and James Brown.

Nobody was writing, singing, or performing anything like Mississippi Goddam.

For one, most of those soul giants were focused on what was straightforward and lucrative. In and outside Motown Records, most successful Black recording artists had no desire to bite the hand that fed them. Simone herself puts it well when describing the necessity of silence in navigating her childhood during the Jim Crowe South: “To break the silence meant a confrontation with the white people of the town.” And the price for that confrontation, she asserts, was death. Murder. That cost was standardized across every means of Black existence we had. Your able body, your home, your career, your social life: the price of confrontation was death. Straight-forward success— money, academy awards, glamour, televized performances— all that depended on making sure to keep quiet about all the bodies in the trees, on the streets, noosed and beaten with billy clubs and blown to bits.

A note from the author, ismatu gwendolyn: maybe it’s because I grew up poor (the only thing I aspired to was regular meals), but I have always found Black capitalism unflinchingly paradoxical— a reliance on the paper or digital money that was once ensured by our literal, physical, fungible bodies. Black people were the original capital under capitalism, but now we’re meant to believe that acquisition of those same US notes of currency (made of cotton, the jokes write themselves) remains the highest aspiration of freedom to strive for. That’s what I get from listening to the music, watching the press of the time, and even the press now— better to be alive and successful rather than beaten up in those messes down south. Best revenge is your paper and all of that. Makes my ass itch, personally.

However, lots of Negroes were sick of suffering under poverty. Some of those Negroes had gotten two proper nickels to rub together and make something of themselves, and they weren’t tryna screw that up. I get it. And so, nobody was singing Mississippi Goddam. There was, of course, say it loud, I’m black and I’m proud! but not yet. That wasn’t until 1968. Atrocity after atrocity descended from white, reactionary settlers onto their enslaved, subordinated, how-dare-you-reach-for-sovereignty Black masses, and everyone was thinking it. But no one said it, and certainly no one sang it; no one was going to risk the sort of career death, fiscal death, social death that comes with confrontation like that. No one, of course, but the bold, the abused, the angry Eunice Waymon— on stage known as the superstar Nina Simone.

She said, “The name of this tune is called Mississippi Goddam, and I mean every word."

Promotional records sent out of this track were returned to the studio, smashed in two. The song was banend in multiple states across the south. Nina Simone was threatened regularly, with her life, by white supremacist domestic terrorist groups if she continued to sing this song. And yet! On she sang. All of her music in this time period became protest music. All of it. She stopped singing about loves and blues and easy baby what have you’s. She sang music written by Langston Hughes— including Backlash Blues, which had lyrics against the Vietnam war draft. She wrote music for Lorraine Hansberry’s play, To Be Young, Gifted and Black. Simone and Hansberry were the dearest of friends.

[Audio from What Happened, Miss Simone?] Nina is on stage, 1969, reciting a poem by David Nelson (part of the Black Nationalist poet activist group, the Last Poets). She wears a v-neck yellow dress and braids honeycombed up, complete with big metal earrings. She asks a multigenerational Black crowd if they are ready: “Are you ready…to do what is necessary to do? Are you ready to Kill if necessary? Are you ready to do what you have to do to create life? Are you ready to smash white things? Are you ready to build Black things?

One thing that every good empire needs is a clear, peaceful plan of succession. Motown had that. The baton was passed down delicately, swiftly, through the Jackson family, to the Carters, and now the current class of young, gifted, superstar Black women rappers are being groomed for takeover. Smooth, easy, lucrative succession. Always radical enough in messaging, in symbolism, to be able to appeal to the ever toiling Black masses. Decidedly never radical enough to bite on the hand that feeds them: white executives within the business of music ownership and distribution, and white consumers who bought their records.

The revolutionaries of the last civil war— the fight to establish the Republic of New Afrika within the United States— simply could not plan for peaceful succession while engaging in armed struggle for the birth of a sovereign nation. How? How do you convince your children, your children’s children, hell! even yourself, that all the fighting, blood and dying was worth continuing for? There is no retirement plan for revolutionaries. You simply have to pray to whichever god you fear that the desire to take up that cursed mantel will infect someone down the line, like a virus, a parasite that crazes you enough to want to stake everything that you touch: your home your clothes your kids your food your blood your movement your body your sanity everything, you stake everything touch on the chance of some true, true freedom. Rather than this shanty game we all play where everyone never speaks to true confrontation, to the rules of the game.

Simone asserted that the duty of an artist is to reflect the times. Below is a quotation from her interview with Black Journal, originally running in 1969.

“An artist’s duty, as far as I am concerned, is to reflect the times. I think that is true of painters, sculptors, poets, musicians, I– as far as I am concerned, some concerned, it’s their choice. But I choose to reflect the times and the conditions in which I find myself. That, to me, is my duty. And at this crucial time in our lives, when everything is so desperate, when every day is a matter of survival, I don’t think you can help but be involved. Young people, black and white, know this– that’s why they’re so involved with politics. We will shape and mld this country, or it will not be molded and shaped at all anymore. So I don’t think you have a choice— how can you be an artist and not reflect the times? That, to me, is the definition of an artist.” –Simone, 1969

I want to point to something that she said: I choose to reflect the times and situations in which I find myself. Not every Black artist found themselves in revolution— among, maybe. Floating above. But they certainly did not choose to be in it. Eunice Waymon, with the power and the stage of Nina Simone, chose to be a revolutionary. She performed Mississippi Goddam at the Selma march, Martin Luther King Jr. looking at her in the front row crowd, the National Guard, equipped with guns, on either side. Simone chose to perform Four Women despite the widespread controversy. She chose her fight. She chose her struggles. She committed to it 100%, and she lived with the consequences of that choice— of the deplatforming, the limiting of your star, of watching your friends be murdered, of living to be the one of the last standing from a breath of history where everything could have worked out different. Do you know how disconcerting it is, how maddening it is, to live every day for a birth of a new world and receive a stillborn? What do you do? Where do you go? Where is safety? Where is freedom?

“I’ll tell you what freedom is— no fear.”

Everyone wants to be Nina Simone, with their Panafrican flags hanging listlessly in their music videos and their fight songs about freedom being used for the next president of the United States of America— absolutely no one wants to sing Mississippi Goddam.

That’s just it, isn’t it? We’ve arrived at the reason I wrote an essay madly, maniacally, in one sitting with a busted finger to boot. I have seen critique after critique that our contemporary Black artists do a poor job of reflecting the times. I think we are liars. These artists are reflecting the times— we just don’t care for our own reflection.

I said this in a TikTok that got slapped down by the algorithmic overseers, the sound banned immediately for some violation of community guidelines. (Side note: it always interests me who I am and am not allowed to bite on with that app. Queen Elizabeth II, Henry Kissinger, and Beyoncé Knowles Carter, all off limits. Can’t write better jokes). I placed the audio of that TikTok at the beginning of this read, but I wanted to highlight those ending theses: we love the taste of artificial radicalism because, in the position of cultural and monetary power and authority, most of us would do the exact same play.

Power does not corrupt, it clarifies.

Beyoncé Knowles Carter and her husband, Sean Carter are the monarchs in reign of the Black music industry at the moment. I fully acknowledge their legendary contributions to culture, to music, and to the artists who come up after them, inspired by them. One of my own first major cultural memories was watching the “Crazy in Love” music video on MTV at my cousin’s house! The legacy is magnificient and full of the same contradictions we face in our lives here, outside of the glittering powers and perceptions of the Rich and Famous.

Example: Mrs. Carter (rightfully) received criticism for her company, Ivy Park’s use of slave labor to make clothes she charges triple digit USD figures for. How is that acceptable from someone that markets herself as a feminist? How is that acceptable for someone who highlights how much Beyoncé TM would not be able to happen if it were not for her team? How are those seamstresses not considered a part of your team?

Dr. CBS, Dr. Charisse Burden-Stelly, makes incredible critiques of Western capitalism, particularly black girl boss Western capitalism feminism, in which freedom always means money. And it always means money for the working class, for the upper working class in the Western world. It never means even economic liberation for those in the third world, that servant class, because the first world working class depends on being able to step on those in the third world serving class to be able to ideate girl boss feminism in the first place. So we have a figure like Beyoncé Knowles Carter, who highlights the importance of her team, who constantly talks about her mother who's a seamstress– when she would never allow her mother to work in the conditions that Ivy park seamstresses slave in! For triple digit U.S. figure leggings. How is that acceptable?

And also, how many of us have bought brand new fast fashion in the last year, knowing how much exploitation goes into the making of Western consumable garments? How are we different? I understand that we have less power, but power does not change you nor does it galvanize you to do better. Power does not corrupt. It clarifies.

So what we're seeing is Shein hauls on a billionaire scale.

Example: She and Mr. Carter (rightfully!) received critique for crossing a picket line and hosting an annual party at the Chateau Marmont Hotel in Los Angeles, to then follow this stunt up with lyrics on her next album about how hard people are working at their nine to fives. That is hilariously horrific. They’re billionaires.

How many of us still did our holiday shopping with Amazon, despite the fact that their unionized workers were on strike?

Power does not corrupt, it clarifies; with power comes larger ripple effects to any decision. We on the ground, within the masses— are we making different decisions? Why do we think we would magically have different, more liberatory ideals with more money? Especially when more money means far greater personal consequences should you align with anything truly radical?

The Mythical Black Artist— this powerful, platformed, extraordinarily gifted artist we crave to glean hope from— is not an artist at all. Art is only the shape of the vehicle. The stage only serves as a means of distribution. The person, the people we yearn for are revolutionaries. And we know these people on stage, awarded and applauded by the Academy, never biting the hand that feeds them (and, in fact, crave the applause)— we know they are not that. We pine and clamour and long for revolutionaries who are powerful enough to become who they are: authors, speakers, musicians, playwrights, civil leaders, chefs, etc. We want powerful revolutionaries.

So why do we accept powerful Black capitalists, who, having become artists, cosplay as radical?

I cannot understand why we accept that.

Nina Simone was not radical because of the art she produced. She was radical because of the life that she lived and the art that she produced reflected the life that she lived. It is only natural for the art that an artist produced. And I'm saying this also as an artist, the art that I produce, the art that he, she, me produces, okay? It reflects the life that you are living. Nina Simone was a radical because she chose to be. And then she produced radical art. So the mythical black artists that we are longing for, the one who speaks truth to power, the one who names The Times with intrepid, bloody realness? What we are looking for is a revolutionary who happens to be an artist. And what we have settled for are black capitalist, cause playing as revolutionaries to sell you things. It's insidious.

There's not a better word for that.

And what is so interesting to me, especially about The Carters, about Kendrick Lamar, about Megan Thee Stallion and those being groomed to take the Motown baton, those who dream of being in the executive suites and offer us an analysis of their hypocrisy where their material radicalism should be as some consolation prize— what is interesting to me is how much they posit themselves to be right beside, just adjacent to radicalism.

The one kind of love from the people that is truly unconditional, truly legendaric, is the love of a people towards their dead freedom fighters. What a hollow love it is when they are alive, because they push us (The People) outside our comfort zones– but once they are shot to death, decayed in dungeons for decades, medicated for demons we politely turned our gaze from until they cannot play piano anymore… once they are dead and gone? Oh, how we love them.

It is my most consistent, most arduous belief that one of the reasons that fake radicalism sells so well is because we actually do not want to pay the cost of true and proper radicalism. It is so much easier to iconize, deify revolutionaries once they’ve died and can’t speak for themselves than it is learn to be like them. To take them off that pedestal, to study their blueprints, and to take up that mantel. We like it when true liberatory struggle is chopped up, processed, and then sold back to us in teeny little plastic coated candied pieces because that’s what we want. We want to pretend we can buy our liberation in peace. Doesn’t that feel so easy? To buy our bodies with the same cotton paper that gleans its value from our labor? Paradoxical. A damn mess. We know that’s not the case. We know that’s not the case! But damn, those songs are just so catchy. And who’s tryna get shot anyways?

Black capitalist benefit from revolutionaries. I cannot say that revolutionaries benefit from Black capitalists. The charity model is fine and dandy, if not tired— Black folks with money money giving quietly to families who had a member lynched by the police, They are typically the first to turn their backs, keep their pocketbooks tight and their lyrics passable across races. But when it comes time to struggle, time to die, and the weaponized state infiltrates communities, kidnaps people from their homes, shoots them dead in their beds, picks them off one by one…

Everyone inspired by Nina Simone. But did you see how she lived? Did you see what that cost her? Everyone wants to be Nina Simone. Don’t nobody wanna sing Mississippi Goddam.

I hope the work of your day galvanizes you for tomorrow.

or simpler said:

peace.

ig

(apologies for not sending this yesterday!)

Member discussion